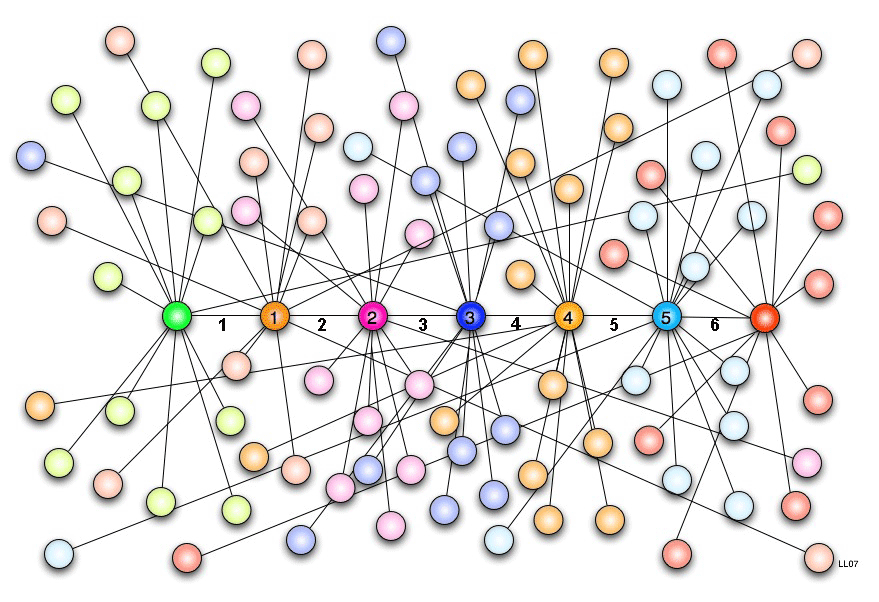

The theory that, through a chain of friends and friends of friends, we can be connected with any other person on earth through a maximum of six steps, was first posited by Frigyes Karinthy. Known as Six Degrees of Separation, this idea was popularized by a 1990 John Guara play and turned into an Academy Award–winning film starring Stockard Channing in 1993.

One of our favourite artistic instances of this phenomenon is the seemingly infinite number of connections that can be made by beginning with Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness. This short novel has inspired numerous adaptations and critical debates over the past century, and while not everyone is a fan of Conrad’s portrayal of colonialism in Africa (see Hugh Curtler’s Achebe on Conrad: Racism and Greatness in Heart of Darkness), there is no denying its influence on popular culture. In honour of what would have been Joseph Conrad’s 156th birthday, we’re taking a look at the far-reaching effects Heart of Darkness has had on the artistic world.

1) Heart of Darkness

The fame of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness reaches far beyond what you may expect from a short novella. However, by using highly memorable metaphors (who doesn’t remember discussing the meaning behind the “white sepulchre”?) to describe the life of an ivory transporter in Central Africa during the height of European colonialism, Conrad crafted a story that has stayed relevant through the years. The pairing of our protagonist Charles Marlowe with his great white whale, Mr. Kurtz, forces readers to question their notions of what constitutes a barbarian society versus a civilised one. It’s no wonder that this complex work exploring colonialism and racism has been used time and again as inspiration for works questioning the right of one society to impose its rules and values on another. Perhaps the most famous example of this is Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now.

2) Apocalypse Now

In Apocalypse Now the Congo River has been replaced by the Nung, but the core characters of Marlowe and Kurtz remain much the same. In the film, Marlowe becomes U.S. Army Captain Benjamin L. Willard, who is tasked with tracking down renegade Special Forces Colonel Walter E. Kurtz in the jungles of Southeast Asia. It’s not just the spirit of Heart of Darkness that pervades the film though, as the influence of T.S. Eliot’s poetry is also highly felt. As Willard finally arrives at Kurtz’s camp he is met by an American freelance photographer who describes his own interactions with Kurtz by quoting “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”: “I should have been a pair of ragged claws/Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.”

3) The Hollow Men

It would actually be quite easy to link back to Heart of Darkness from T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Hollow Men.” Shortly before (spoiler alert) Colonel Kurtz dies in Apocalypse Now he begins an Eliot-inspired soliloquy. Not only does the man characterised as being “hollow at the core” briefly recite “The Hollow Men,” but his desk is home to the books From Ritual to Romance and The Golden Bough, both cited by Eliot as chief inspirations for “The Waste Land.” It’s at this point in our degrees of separation that we could conveniently loop back to Heart of Darkness, as Eliot’s original epitaph for “The Waste Land” was a passage from Conrad’s short novel. However, for the sake of going as far as we can in six steps, let’s see where else “The Hollow Men” can take us.

4) The Gunpowder Plot

Kurtz is hardly the only hollow man that influenced Eliot’s poetry. In fact, Eliot himself is thought to be one of the lamented men in his famous poem as he struggled with the fallout of his failed marriage to Vivienne Eliot. There are two famous epigraphs added to “The Hollow Men” that point to the various writings that clearly influenced Eliot as he composed his poetry. The first, “Mistah Kurtz – he dead” points us back to Heart of Darkness, while the other, “A penny for the Old Guy,” speaks to Guy Fawkes, the man whose effigy is burned in Britain on the fifth of every November. Fawkes was a main conspirator in the 1604 “Gunpowder Plot” to assassinate King James of England, and for his treason he was dragged, drawn and quartered as a manner of execution. In the years following the assassination attempt, the King’s supporters began lighting bonfires in celebration of his escape from harm and this ritual has evolved into the burning of effigies bearing Fawkes’ face. The image of his powdered and mustachioed visage has become a powerful cultural symbol of resistance and anarchism.

5) V for Vendetta

Though possibly better recognised now as the symbol of Anonymous and the Occupy Wall Street movement, the Guy Fawkes mask was first brought to the wider public consciousness by Alan Moore’s 1980s graphic novel series (and the 2006 film adaptation) V for Vendetta. The V for Vendetta story takes place in a dystopian United Kingdom ruled by a totalitarian government, and tells the story of a mysterious masked revolutionary who calls himself “V” and a young woman named Evey who becomes his protégé. A three-part series, V for Vendetta’s third book is titled “The Land of Do-As-You-Please,” the name given to a society V pictures as being functionally anarchist (as opposed to the current state of “Land of Take-What-You-Want”). These names are derived from a book that V reads to Evey to help her sleep – the very real novel The Magic Faraway Tree.

6) The Magic Faraway Tree

Somehow, here in the sixth degree of our journey, we find ourselves connecting Joseph Conrad’s bleak and provocative look at imperialism with a pleasant and fanciful children’s book. By creating various lands for children to explore, including The Land of Do-As-You-Please where anybody can do what they want and have great fun, the book’s author Enid Blyton has unexpectedly become a rather popular figure in the anarchy movement. Perhaps even more surprising, for our purposes, is that The Magic Faraway Tree has been ranked as number 66 on the UK’s Big Read list of top 200 books, outranking Heart of Darkness by 92 spots!

What kind of fun can you have by playing Six Degrees of Separation? Have you ever been surprised to find a connection between two seemingly unrelated works of art?